Can selfishness be intersectionally liberating? Can assholes help to free strangers?

Those are two sentences saying the same thing, and I’m being repetitive only because I feel like I’m going to be fighting both of those conflicting impulses while I write this whole thing. Sometimes my philosophy degree is more trouble than it’s worth.

I’d say the same tonal conflict is true for this cinematic masterpiece One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest. At its surface, it’s just a story of a randy-horny good ole boy trying to stir up trouble at a mental institution and have some fun, until he gets smashed by some know-it-all in a white doctor’s gown who’s never known real human joy in her whole suffering life. On the other hand it’s a weighty allegory for the challenges and depths and risks of human freedom, with undercurrents of messianic allusions on the main character.

But all these things have already been written about this movie & book (I know, I read most of them; I was nuts about this book & its author Ken Kesey for quite sometime in college—Hunter S. Thompson too obviously; I must obey the inscrutable exhortations of my basic-ass white boy soul). Other than the old things about this movie, what is new about it—obviously not because the movie has changed, but without changing is the movie still pertinent to modern age? Do we have new characters currently that are reflected in the old characters back then, falling into a future that the creators from decades ago were unknowingly reflecting now, because time & its art is a pair of flat stupid circles?

Worth first obvious mention—it’s always been cool to not trust the government & to piss off authority. But why is Randle Patrick McMurphy so much more whimsical about his rebellion than the current crop of illiterate face drooling plague rats we’ve been cursed with? Was it just “the 60s?” I’m going to say, probably not. I’m willing to bet my last 41-year-old Square dollar that there were more than enough jingoistic racists floating around San Francisco & Woodstock. They were just luckily never in charge of the microphones & bullhorns.

But upon my contractually obligated re-watch in order to weave this essay, I’m struck with how OFOTCN can still act as a skeleton key of some sort for our current fascist malaise, at least as far as recruiting the unrecruitable & accidentally helping the ignored and marginalized without direct intent. What if being a bored, selfish cur with ADHD and a deck of porno playing cards was a legitimate route to metaphorically knocking down the walls for everyone else on your way out of the smashed windows you shattered on your way to Canada?

As far as first monikers go, it’s important to mention that Randle Patrick McMurphy is initialized to RPM—revolutions per minute, which you might accuse me of being cheeky except for the fact that Ken Kesey has mentioned in numerous interviews that he intended that directly as Revolutions Per Minute, which is somehow both the most subtle and also the most ham-fisted thematic metaphor I’ve ever read. The Randle character is intended to be a living avatar of the aphorism from Albert Camus (an author even better than me & Ken Kesey combined, if you can believe that), “The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.” That’s all a given, that’s symbolically presented on a silver platter for anyone watching the movie. That part’s easy. My question is, can a character who’s living all this freedom only for themselves inadvertently foment the liberty, freedom, and independence of those around him without even trying, or in fact even giving a shit? Like a rising tide in a leather jacket that accidentally also lifts all the boats around it.

The movie wastes no time letting us know that RPM thinks quite highly of himself. He’s a “marvel of modern science” when the doctor asks him if he thinks there’s anything wrong with himself. Certainly an answer drenched in shamelessness and self-acceptance, obviously contrary to the entire energy of the literal building and all its inhabitants and staff and tiles and formica and glass and concrete right down to the foundation. He’s so irrefutably chipper about (only) himself, that even when he fails to lift the sink in the wash room, he drops the utterly savage line that “I tried didn’t I? God damn it at least I did that” right in the faces of all the men who just watched him fail. Even failure is a victory for his irrefutable faith in himself. A victory while stuck in this emotional gravity sink of an edifice ergonomically designed to make its inhabitants hate themselves.

But for the whole first half of the movie, we can tell he’s only doing any of this for himself. Out of boredom. To kill time since it’s saving him from the work prison. And anything that contributes to that boredom is verboten to him. That’s his only priority. He doesn’t want to watch the World Series because it’ll “help the boys” and “their struggle is his struggle.” It’s because he just likes baseball. He hasn’t thought any further than that. The same is for his “bet” to wind up Nurse Ratched until she doesn’t know whether to “shit or wind her wrist watch.” As if he needed the boys to egg him on. He would have hassled her for free without an audience. He’s not taking on a Goliath in order to “pursue intersectional liberty for his fellows in solidarity with their incarceration.” He’s bored out of his ass. And he’s likewise shortsighted enough that he doesn’t even consider that there might be consequences (for himself) to his 24/7 game of treating human beings like his own personal fidget spinners.

This is ramped up & revealed at the group therapy session near the middle of the film, which devolves into a screaming match, smashed windows, and a riot for cigarettes. Blowing well beyond Ratched’s control, and Randle finally for once understanding there are stakes here that he hadn’t noticed up until then. This is reiterated when they take Cheswick away for electroshock therapy; RPM isn’t exactly consoling. He mostly feels confused & hassled that Cheswick is holding on to him for dear life. But he immediately wakes back up when Chief Bromden reveals that he’s been playing a fast one on the whole building by only pretending to be deaf & mute.

And this is the beginning of RPM learning to care. When he has a friend. When he has someone keeping his own secret, that he shares with RPM. Chief Bromden is the introverted version of the Camus quote—he is living in pure rebellion every second of every day to every single person around him. And the honor he bestows on RPM by letting him (and only him) in on it. And RPM is literally giddy AND flattered. Someone had one over him, even HE thought Chief was a deaf mute. RPM is ecstatic to be outsmarted by someone else for once. Someone else is running a grift. Now he’s not a solitary grifter. And the loneliness of that lifestyle– marching to your own drum can be exhausting if no one else hears the music—finally punctured by one person who’s finally doing the same thing he is.

Now this sets us up for the second half of the movie, when RPM actually starts taking an engaged interest in the other lunatics. He actually cares about their development. Having one friend actually taught him how to care about everyone else. The re-introductory scene begins first with Sefelt lying to Nurse Ratched to cover ass for Fredrickson—reminding us that friendship can be two people willing to lie to other people for each other (especially to the cops). Then the first wink to Chief Bromden from RPM before revealing his newly electrically invigorated mental health to the rest of the Mental Defectives.

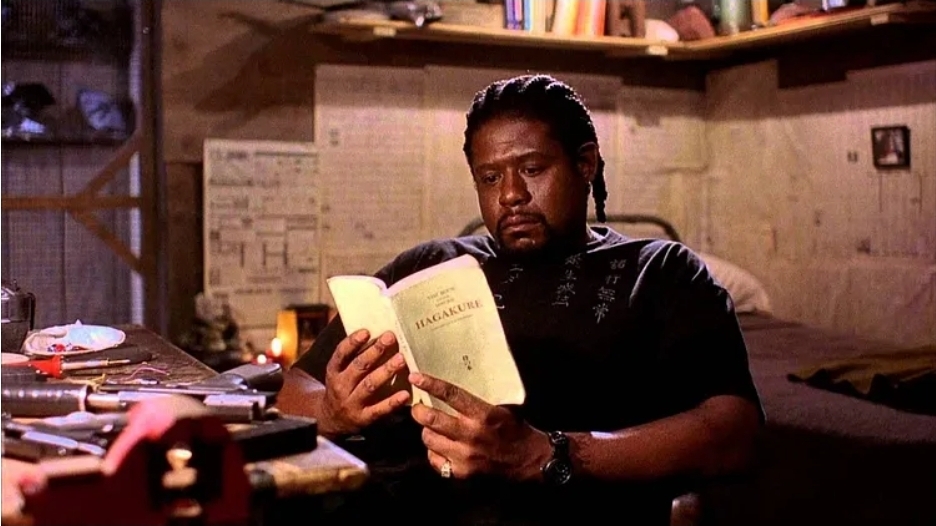

You’re all adults with impeccable cinema tastes, so I know you’ve all seen the movie already, so we all already know how the story plays out (with the book actually ending with all the self-committed inmates actually electing to set themselves free, which nicely plays into my theme much better, thanks Mr. Kesey). What’s important here is that we have no indication that RPM is, let’s say, woke enough to explain what he was doing or why he was doing it. RPM is many things, but I don’t think “reader” is one of them. I don’t think he’s read Marx, he does not understand praxis, solidarity, or any of the other utterly insufferable lexicon from the Communist Reader at my feet covered in sand grains from my one-eyed pirate cat’s shit box. RPM did not need–and in fact would not have sat still for—any intellectual convincing, and a library card would have been wasted on him. As I said before, he didn’t even register “wrongdoing that required heroic rectitude!” He was just dying of boredom. And he didn’t know boredom was everyone’s problem until he had made a friend. And he doesn’t know that boredom can actually give you a mental illness—he’s been lucky enough (to be born with enough moxie & born white– let’s not pretend that doesn’t buy him leeway with authorities) to be able to fight against it his whole life. And most control-cultures have a vested interest in making their inhabitants bored: I’m reminded of La Haine where boredom literally leads to paranoia and violence, which is lashed out upon one’s surroundings and fellow travelers in your immediate vicinity—it almost never goes up the chain of command. This is shown in OFOTCN in the first group therapy session, when the inmates are egged on to verbally attack each other, instead of unifying against The Nurses—one of the course-corrections that RPM eventually, inadvertently, drives them towards with his ne’er do well-ery.

But by the end of the movie, does all this actually portray an actual change of heart for RPM? I don’t know. True to form, I don’t even think he knows. He sits in the chair, waiting for Billy to finish banging Candy. Does he care? Is he perturbed? Is he thinking desperately about how to save everyone else? Is he just too drunk to climb out a window and just needs to rest his eyes for a minute? After Billy dies, why does RPM try to choke out Nurse Ratched? Is it “for Billy”? Is it because he feels guilty for Billy’s death and he’s projecting? Is he just sick of her always telling everyone to remain calm? Who knows. All we know is that it happened. It’s what his reflexes told him to do. And they’ve got him this far in his life, and you dance with who brought you, so he followed through on them. I wouldn’t even say “consequences be damned,” because that implies he even considered those at all, which we know is not his forte, to say the least.

Then the denouement at the end of it all. The Nurse’s neck brace (showing she’s not invincible). The lobotomy. Chief Bromden’s act of rescue (there’s a wonderful little quick cut-in shot where Chief is undoing his own bed straps by himself, just to cinematically remind you of RPM’s influential effect on those around him). Chief breaking the sink off its foundations, setting the water free from the pipes & himself free from the window. But it’s ultimately Chief’s liberatory act of murder, his reciprocated endowment of freedom back onto RPM that is the greatest act. The smashed window leaves a path for the other inmates, but whatever has happened to all of them, because of RPM, will spread to anyone else they run into, for the rest of their lives. Solidarity doesn’t begin to describe it. It’s more like a pathogen they caught from him, that you use as a vaccine to fight the greater disease of boredom. They’re all inoculated now.